Making Special

Why Art Will Save Us

There are several ways to start this article. I could talk about the neuroscience of aesthetics.

I could discuss attention, focusing on hemispheric differences, and how they pay different kinds of attention to the world.

I could cite recent studies about the cognitive decline associated with social media and smartphone use. How simply quitting their use for thirty days provides the equivalent of weeks of successful behavioral therapies.

I might choose to focus on the cultural divisions emerging from people’s inability to entertain multiple truths simultaneously.

Instead, I’ll write about the benefits of moving your body imaginatively because it is easier to implement. Think of it as a micro-revolution.

Imaginal Movement

I first discovered the joys of movement at age six as a young gymnast. Throwing my body around with giant mats to cushion the blows was a phenomenal way to explore the limits of movement without severe consequences or instructional repercussions. However, I did still get routinely kicked out of 2nd-grade class for tapping my pencil incessantly.

When I was in 7th grade, I was cast in a production of Thornton Wilder’s classic dream-tale of American life, Our Town, as Editor Webb. Pretending to be a middle-aged newspaperman, discovering the right waddle/walk, holding a facial expression of dour severity, and developing a penchant for delivering bitter sarcasm were highlights of the experience. My best friend Josh was cast as George, the protagonist of the play. In our only shared scene, he waits impatiently for my stage daughter, Emily, while I read the paper in the kitchen.

We came up with a bit of stage business: I would read an imaginary newspaper, held aloft in front of my face, and he would become engrossed in an article on the paper only visible from his seat across the table. To see it more clearly, he would lean across the table to read more closely, his face inching nearer to mine until I pulled the “newspaper” away to speak directly to him, surprised to find his face directly in front of mine. He pulls away, shocked. I’m not impressed. Hilarious.

You might imagine how difficult it would be for two middle school-aged boys to keep a serious face while mugging this charade. Although we broke into endless laughter during rehearsals many times, during the performances, we were expert performers, committing to the bit and showcasing our imaginative flair for the audience to appreciate. Still, we inhabited a space for a moment that was separate from the linear flow of time, suspended in kairos: a cyclical, returning moment of renewal and possibility.

I went on to pursue a career in professional theatre, eventually joining a small company based in Seattle and traveling around the world, making imaginary worlds come to life before hundreds of thousands of people, winning awards, and teaching others—from elementary school children to seasoned professional actors—our tools and techniques for imagining and inhabiting these wondrous places through the power of embodied imagination. Now I teach leaders, teams, and individuals how to use these same tools to reclaim attention, embody imagination, and regain agency amid our myriad meaning crises. The hardest part is convincing people to let their guard down and remember how to play. How to make each moment special.

Making Special

The anthropologist and scholar of evolutionary art-making, Ellen Dissanayake, identifies the creative impulse, or “making special,” as an intrinsic part of human nature. For Dissanayake, art is a ritualistic act that binds people together through shared meanings and values. It is not an accessory, but central to our evolution as what she calls Homo aestheticus: humans who make art. Distinct from Homo faber (humans that make), our long standing ability to create special artifacts of imagination generates a specific kind of meaning that cannot be replicated anywhere else.

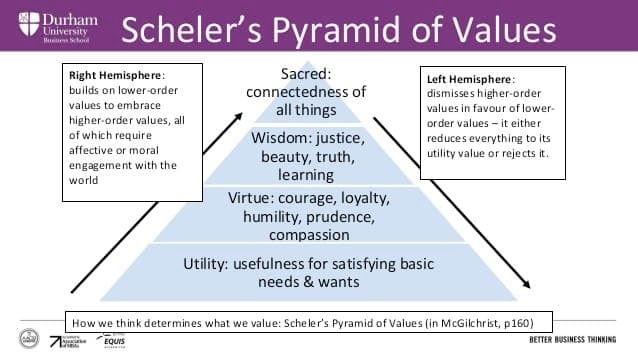

This is, of course, the primary function of sacred play or religion: to generate a deep meaning and connection to the sacred. The neuroscientist and psychologist, Dr. Iain McGilchrist, whose hemisphere hypothesis forms the basis of much of my work, is fond of citing Max Scheler's philosophy of a hierarchy of values. This framing underscores the importance of distinguishing between types of attention inherent in our evolutionary biology—the tension of opposites that forever pulls our focus between two poles.

Embodiment, or an ‘ecologies of practice’ as Dr. John Vervaeke puts it, strengthens our ability to get back into our “right minds”—literally.

This ability of ours to make special points to a lost technology, and one which Nietzsche anticipated in that eerie way of his. He wrote in Dawn of Day, #265:

There is a time for the theatre. If a people's imagination grows weak there arises in it the inclination to have its legends presented to it on the stage: it can now endure these crude substitutes for imagination. But for those ages to which the epic rhapsodist belongs the theatre and the actor disguised as a hero is a hindrance to imagination rather than a means of giving it wings: too close, too definite, too heavy, too little in it of dream and bird-flight.

We’ve lost the ability to dream, as a people in general. We see this in our crude substitutions for imagination and the banality of our aesthetic landscape. Now is a time for this “making special.” It is necessary in order to reclaim our origin stories, our myths, our legends, and our connection to the sacred. Even the impulse toward cynicism I feel in writing this sentence is proof enough of the dire straits in which we find ourselves, if indeed we try to look.

You’re In Danger—Look Up

The recent movie "Look Up" attempted to shake our heads loose from the news cycle and show how apathetic we have become under the threat of the oncoming, blazing meteor of technofeudalism. You may notice how hard it is to doom scroll and walk at the same time. It is equally challenging to resist the onslaught of fascist tribalism while looking at TikTok videos and Instagram feeds.

At one time, Facebook played a significant role in fueling the Arab Spring. It actively dissuades this type of connection now.

Embodiment directly opposes the illusion of choice offered by the online environment.

What we mean by embodiment is the “re-homing” of our intelligence within the framework of the body: our Soma. Soma is Greek for body. It is our environment. Just as we are part of, not separate from, nature, so our intelligence is of, not distinct from, the body. It is easy to slip into the self-deceptive language that we “have” a body. It is more accurate to say that we are a body.

To call our body an environment does a disservice to the word. “The Environment” is not something differentiated or other that we “protect” or “return to.” These are persistent illusions born of our left-hemispheric need for utility and power. As we are starting to remember, there is no differentiation between material objects at the quantum level. We exist in a massive spectrum of inter-being. The work of the artist is to reorient our senses and intuition back to this fundamental truth: life depends on our participation, our belief, even.

What To Do

The path forward requires an embodied rebellion—a conscious choice to fully inhabit our sensory and imaginative capacities, despite the persistent pull toward disembodied consumption. This isn't about retreating into nostalgic theater games or rejecting technology wholesale. It's about reclaiming the fundamental human capacity to make meaning through presence, to transform ordinary moments into occasions of depth and connection.

When we move imaginatively—whether through formal artistic practice, or simply by bringing full attention to how we walk, speak, or relate—we activate and rewire neural pathways that have been dormant under the regime of algorithmic attention.

We literally rewire ourselves back toward what McGilchrist calls the right hemisphere's gifts: context, relationship, and the capacity to hold paradox without collapse.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Our ability to navigate complexity, to hold multiple truths simultaneously, to generate genuine solutions rather than mere reactions—all of this depends on our willingness to step back into embodied intelligence. The artist's work of "making special" is not luxury or decoration; it is the essential technology for reclaiming agency in an age of manufactured helplessness.

Every moment that we choose presence over distraction, imagination over consumption, embodied engagement over digital drift, we strengthen our own capacity and contribute to the collective recovery of what it means to be fully human.

The question isn't whether we can afford to make this shift—it's whether we can afford not to.

Thanks for the like, L. E. Mullin